How

appropriate that you enter the Columbia River Maritime Museum through the

channel marker buoys.

How

appropriate that you enter the Columbia River Maritime Museum through the

channel marker buoys.Columbia River Maritime Museum - 2008 . . .

during our travels in the

Pacific Northwest

Updated: 11/30/08

The museum presented maritime history through artifacts, fishing vessels, ship models, paintings, photographs and interactive exhibits.

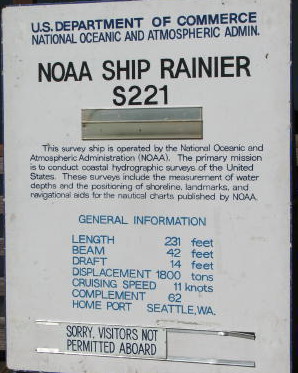

A National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration ship was moored at the dock. The public was not permitted aboard. We were told the NOAA ship comes in every once and a while. This time, workers appeared to be doing some repairs or maintenance. Due to activity on board, we thought they were getting ready to leave.

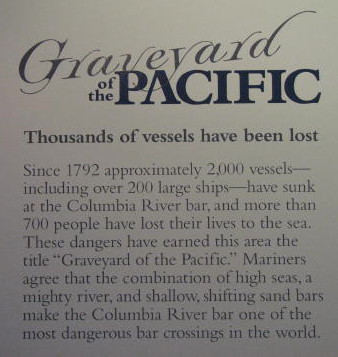

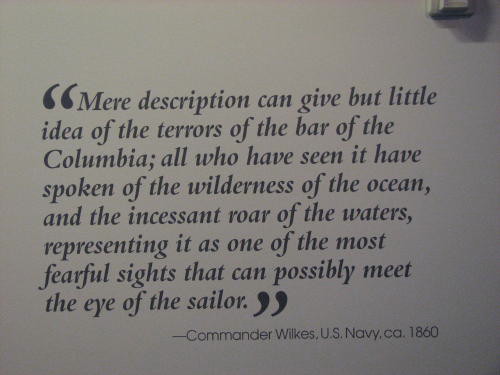

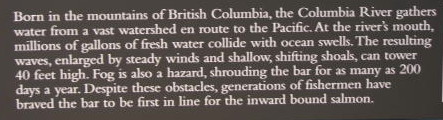

Where the Columbia River 'collides' with the Pacific Ocean has a reputation.

It isn't a good one.

Where the Columbia River 'collides' with the Pacific Ocean has a reputation.

It isn't a good one.

The location of fifty shipwrecks were identified on this map. When the button next to the ship's name was pushed, a light indicated the location of the shipwreck.

It also highlighted the early discovery of the river, salmon fishing and canning, the shipping industry and the Coast Guard.

Everywhere were reminders of how treacherous the bar was.

The exhibits were very well done.

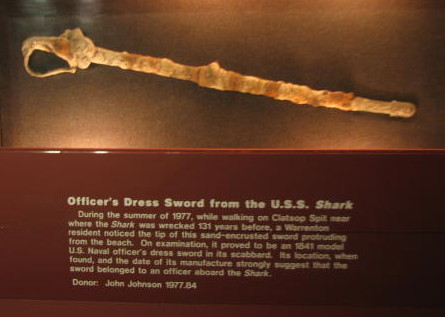

Several of the artifacts in the museum were discovered in the 70s and donated

to the museum.

Several of the artifacts in the museum were discovered in the 70s and donated

to the museum.

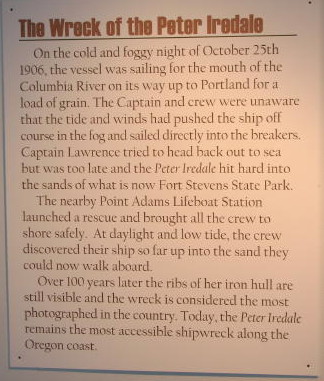

The

Peter Iredale is the ship wreckage that was sticking out of the sand at Fort

Stevens State Park.

The

Peter Iredale is the ship wreckage that was sticking out of the sand at Fort

Stevens State Park.

At Fort Stevens State Park . . .

The sign panel about the Bar Pilot Pulling Boat is an interesting read. The story took a personal turn when Mary Lou talked personally with a former oarsman of a pulling boat. He worked as a kid with his father who was a commercial fisherman. To be an oarsman you didn't need a long training period - you just had to be strong.

Signal devices . . . Lanterns . . .

The Corp . . .

Shark fishing floats . . .

Whaling . . .

How did it fit into the Museum?

After her decommissioning, U.S.S. Knapp was sent to Zidell Explorations, Inc. in Portland, Oregon to be cut up and sold for scrap metal. Mr. Zidell generously donated the entire bridge and pilot house to the Columbia River Maritime Museum. The bridge, weighting 13 tons was barged down the Columbia River, put on a truck, and then placed on the museum site by a giant crane. The building was then constructed around the navigation bridge. The Knapp was a World War II era U.S. Navy destroyer.

This is a painting of the USS Oregon.

Steamships were important to the Columbia River. It was amazing how much wood they burned.

This tugboat and barge was another model. On the Labor Day weekend on the Snake River , we watched the real ones of these working the river.

This looks different from the fenders boaters use today.

This was a beautiful skylight.

The museum had several boats that were donated after their useful life or decommissioning. Mary Lou took a turn at the wheel.

One display had a glass floor made to resemble a walk over water loaded with fish.

These are a couple huge anchors. The fluted anchor has a woman sitting in front of it for size comparison. The mushroom anchor is on the front of the Lightship Columbia.

The Columbia was "on station" about 5 miles offshore, marking the entrance to the Columbia River.

A lightship is a floating lighthouse designed to serve where a major aid to navigation is required, but where the depth of water or other conditions make construction of a lighthouse impractical. A lightship remains anchored in one place to mark the entrance of an important river or dangerous reef or shoal.

For nearly a century, from 1892 to 1979, a lightship marked the entrance to the Columbia River.

The Lightship Columbia crew of 17 worked two to four week rotations, with ten men on duty at all times. Life on board the lightship could best be described as long stretches of monotony and boredom intermixed with riding out gale force storms. Thirty -foot waves were not unusual during fierce winter storms. Even the most experienced sailors got seasick. The light ship did not roll like a regular ship but bobbed like a cork in all directions.

All of the railings were wrapped with rope and varnished. It made them very secure to hold on to.

Radio room appeared to be an active amateur radio station.

Our visit to the Columbia River Maritime Museum was well worth our time. We spent four hours there. The admission was $8 - for seniors admission was $7.

GO BACK TO > > > Pacific Northwest - 2008